There is more to wildlife conservation than meets the eye. On the surface, much of it appears to the mass public as focused towards individual species on the brink of extinction, and for good reason. Using handful of ‘enigmatic species’ as they are called – your pandas and tigers and rhinoceroses, etc. – conservationists are able to canvas mass support for saving entire ecosystems and restoring a balance to nature. In some cases, in fact, saving one keystone species can cascade into a chain of natural events that work towards environmental betterment.

Pakistan has been blessed with its own enigmatic species, each more mysterious than the next. In the north we have the elusive snow leopard, rarely caught on film. The mighty Indus is home to another, even more puzzling creature – the blind Indus River Dolphin, known locally as Bhulan.

It’s distinct eyeless form, that appears in many ways contrary to popular conception of dolphins, is one overt reason for why it has captured the imagination, but so are the many myths that circulate around it in folklore. Its sister species in the Ganges is already considered an emblem of the namesake river goddess in Hindu mythology. But for us, perhaps the bigger question is how a dolphin came to call a river a home in the first place.

But mysteries aside, there has been in recent years a visibly upward trend in the rare dolphin’s population.

Encouraging signs

There was once a time when the Indus River Dolphin was ubiquitous in not just the river it takes its name after but all connected waterways. Indus Dolphin Conservation Centre (IDCC) Sukkur Incharge Mir Akhtar Talpur said the species started moving towards endangered status when the South Asian irrigation system was built by the British in the 18th century. “As the many dams and barrages were constructed to cater to the needs of the agriculture sector, this aquatic mammal’s natural range was disturbed and it was confined between one riverine structure and another,” he explained.

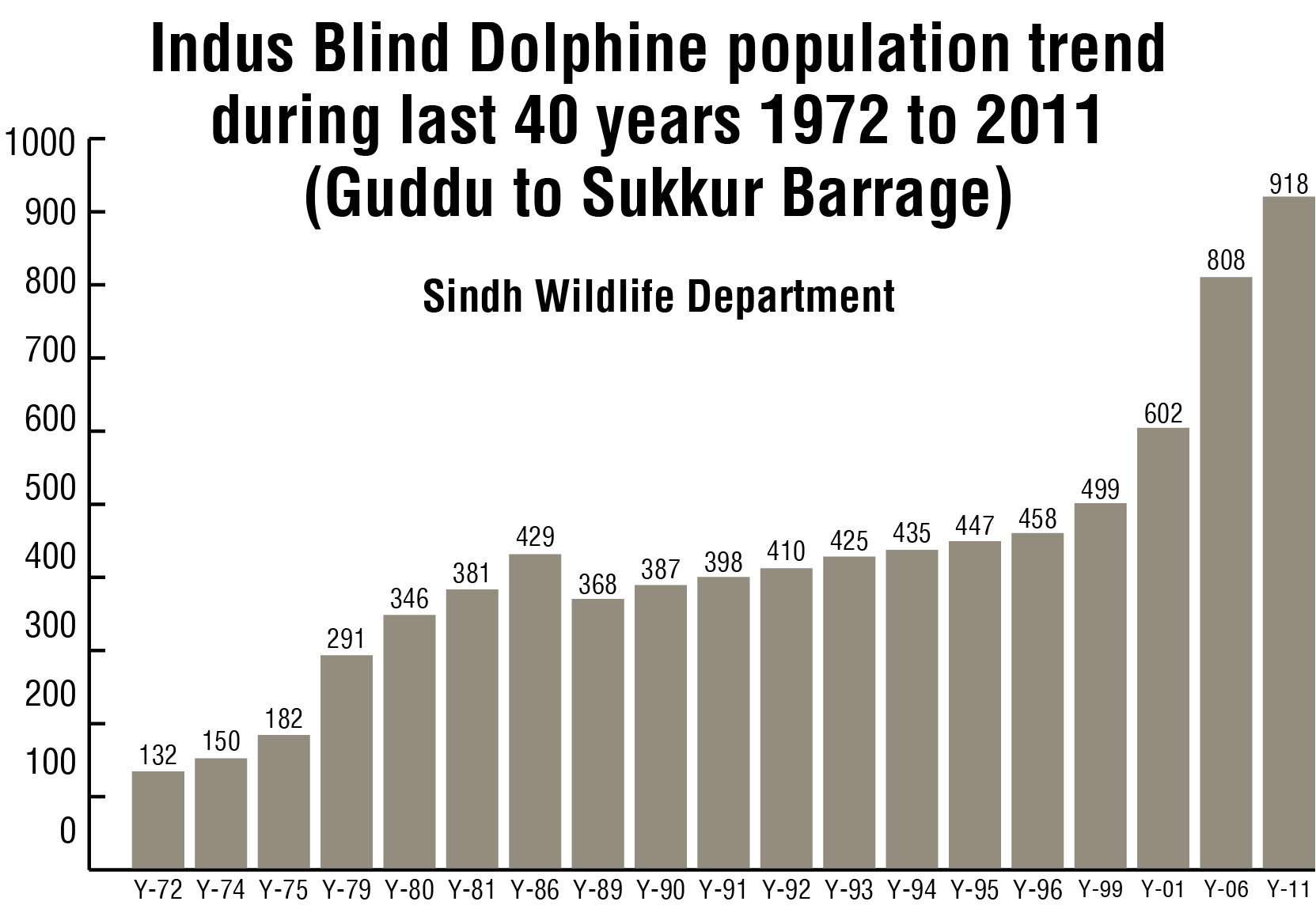

Talpur said the authorities started officially monitoring the numbers of the endangered dolphin with the establishment of the Sindh Wildlife Department in 1972. “The department started routine surveys and since then, we have know the exact numbers of the dolphin in Sindh.”

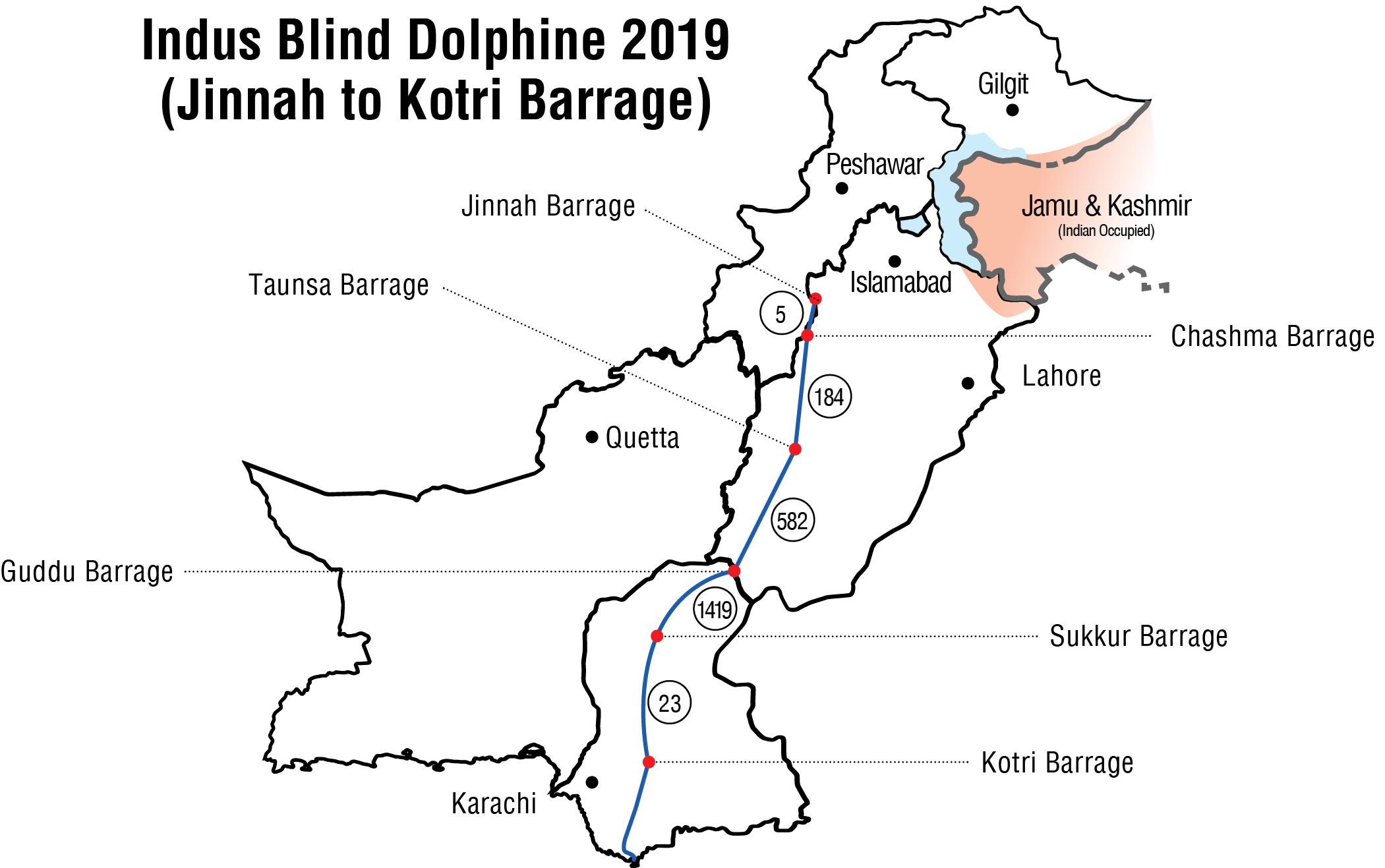

In 1972, when the first survey was carried out, there were just a paltry 132 dolphins in Sindh. “Even so, there has been a steady increase ever since,” Talpur shared. “A 1975 survey showed the numbers had grown to 182. When the last survey was conducted in 2019, we found there were 1,419 river dolphins between the Guddu and Kotri barrages.”

World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) Project Manager for Sukkur Mohammad Imran Malik said that his organisation’s own independent surveys and rescue operations supported the steady rise in dolphin numbers. “Our results have consistently indicated an increase in this endangered species’ population. We know the numbers have been growing since 2001 and it is quite possible this trend began in the 1970s, when the hunting of this animal was banned,” he said.

Sharing the results of their latest survey, Malik said dolphin abundance was increasing between the Chashma and Taunsa barrages, a range where the species population was previously thought to be stable. “Direct counting results for the sub-population between Chashma and Taunsa barrages were 84, 82, 87 and 170 for the years 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2017 respectively,” he shared. “Between Taunsa and Guddu, similarly, direct counts have been steadily rising from 259 in 2001, to 465 in 2011 and 571 in 2017.”

“The last sub-population surveyed between Guddu and Sukkur barrages, which historically hosted the highest population of the Indus River dolphin also indicated a similar significant increase in population from 602 in 2001 to 1,075 in 2017,” Malik added.

Fruits of collective effort

The fishing communities living along the banks of the Indus, particularly the Hindu Bagri community, used to hunt the dolphins back in the day to extract oil from its fat. “They used this oil to cook food, but an awareness campaign initiated by the Sindh Wildlife Department and WWF convinced them and other stakeholders to start taking care of the endangered species,” he said. “Because of this extensive work, members of the riverside communities immediately inform concerned officials if they sight a dead or stranded dolphin,” he added.

WWF’s Malik provided further detail on this participatory approach to wildlife conservation. “We integrate research and effective law enforcement with stakeholder and community engagement,” he said. “Our joint dolphin rescue programme with the Sindh Wildlife Department has been in place since 1992 and has been very effective in rescuing any stranded or trapped dolphins,” he added. Sharing rescue figures, Malik revealed that 131 out 147 stranded dolphins were saved and released back into the river between 1992 and 2017. “Only one specimen could not survive the rescue operation, while 33 could not be rescued at all.”

WWF and the Sindh Wildlife Department have also established a dolphin-monitoring network in collaboration with relevant stakeholders and local communities to monitor the Indus River and adjacent canals and tributaries to save dolphins from other hazards. “The monitoring teams of this network have conducted over 100 monitoring surveys since 2015 to stop illegal fishing and to rescue stranded dolphins with 12 successful rescues during 2016.”

Talking about the steps taken to protect the endangered species, Malik said that a 24-hour phone helpline has been set up to report any stranded dolphins. “The observed increase in the population may be an outcome of all these concrete and continuous efforts,” he said.

Threats persist

According to WWF researchers, habitat fragmentation and degradation due to extraction of water in the dry season and pollution are amongst the prime threats faced by the Indus River Dolphin. Since the 1870s the range of the Indus River dolphin has been reduced to one-fifth of its historical range, primarily due to shortage of water caused by agricultural demands and removal of water from the river to supply the extensive irrigation system in Pakistan.

“Barrages across the Indus River hold running water and divert it into an extensive network of irrigation canals emerging from each barrage to fulfill the need of water for agriculture,” shared Malik. “Indus dolphins tend to move to irrigation canals through flow regulator gates, adjacent to barrages throughout the year and when the canals are closed for maintenance, dolphins are stuck in the canals due to sudden water shortage.”

The WWF official said intensive fishing in the core habitat of the Indus dolphin is also one of the key threats to its population with high probability of dolphin mortality from entanglement in fishing nets, especially when they move into easily accessible and heavily fished irrigation canals. “Habitat fragmentation and degradation due to extraction of water in the dry season and pollution are amongst the prime threats faced by the Indus River dolphin,” he added. “The construction of numerous dams and barrages across the Indus River has led to the fragmentation of the Indus River dolphin population into isolated sub-populations, many of which have been extirpated especially from the upstream reaches of the river,” he concluded.

Most of the big cities of Punjab are situated at the bank of rivers and all the drainage waste is mercilessly released in the river. “Not only this but industrial waste, especially poisonous waste from tanneries, is extremely hazardous for the fragile mammal,” he said. According to him, in Sindh from Guddu barrage to Sukkur barrage, no big cities exist at the bank of Indus, except for Sukkur.

“Yet another reason is scarcity of water in the upstream and downstream from Guddu to Sukkur barrages,” he added. “Ample water is available throughout the year, which is why majority of the blind Indus dolphins are found between the two barrages. The only time of the year when the dolphins face difficulties in surviving is in January during the closure of barrages for annual repairs and maintenance in January.” During those days, cases of dolphins slipping in the canal in search of food are frequent. Upon reports of trapped dolphins, they are rescued and released in the safety of the river.

Talking about the fragility of the dolphins Malik said, “They suffer heart attacks as soon as they are entangled in the fishing nets. Therefore, the fishermen are educated to immediately make efforts to rescue the mammal to save its life.”

Mehram Ali Mirani, an elderly fisherman, strongly condemned the use of poisonous chemicals by some in his trade. “This practice must be stopped because on the one hand it proves hazardous for the marine life and on the other human beings also fall prey to various diseases after eating those poisonous fish,” he said. “We are born fishermen and our survival is linked to the clean and healthy river. Therefore, I request the fishermen community, not to use chemicals to catch fish,” he said.

The Indus River dolphin, one of the rarest freshwater creatures in the world, has been driven to extinction as a result of excessive poaching, water pollution and climate change. It has been catergorised as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature after researchers noticed a significant fall — by more than 50% — in its population.

A dolphin monitoring network was set up with the help of WWF and the provincial wildlife department following a door-to-door awareness campaign with the local fishing community. It is heartening to see the locals actively involved the process. Such sustainable projects are rarely initiated, let alone implemented in Pakistan.

The most significant achievement of this project is that it has changed the mindset of the local fishermen, who viewed these dolphins as a means of earning money rather than as living creatures that coexists together with us. Even though concerted efforts by officials have helped these dolphins survive, the barrages on the Indus River have disrupted the movement pattern of these dolphins, who have had to restrict themselves to a 180km strip of waterway in Sindh. As a result, many often end up in dangerously low water levels. Even though fishermen are now quick to respond and bring them back to open waters, this is not the ultimate solution.

We must do away with any such infrastructure that causes harm to biodiversity. We must do everything within our means to conserve the natural habitat of these animals. In the wake of extinction, we must no longer look at nature and animals as merely resources used to meet our needs. Instead, these animals are a part of the same ecosystem, the same web of life that we are a part of. Once we learn to accept this, our whole outlook towards nature changes. Who knows, perhaps we might be the next in line for extinction.

Stranded Indus dolphin dies

In Nov 2021, another Indus River Dolphin was found dead in Khairpur’s Mirwah Canal.

The dolphin was sighted by the villagers in Ali Nawah Wah, a canal also known as Mirwah, who informed the Sindh Wildlife Department without any delay so that it could be rescued.

The SWD team from Sukkur planned to rescue the stranded dolphin from the water, but they were informed in the morning at 11am that the dolphin baby had died due to “unknown circumstances”.

“We were informed by the villagers that the dolphin had died,” confirmed Sukkur SWD Deputy Director Adnan Hamid Khan. “The cause of death is still unknown,” he said, adding that water in the canal was not deep.

Khan said that an inquiry will be initiated and stern action will be taken against those found guilty. “I do not think anyone harmed the mammal,” he said, adding that a probe will reveal the facts of the incident.

Khan also said that strict action will be taken even against his own team in case of negligence. The rescue team will transport the body to Sukkur Indus Dolphin Sanctuary for further investigation, he added.

This is the fourth death of the endangered Indus Dolphin in 2021, as per the official data of the SWD.

Confirming the mortality, SWD provincial Conservator Javed Ahmed Mahar said that the mammal had died before the rescue operation was initiated. “There is almost no chance to successfully rescue a dolphin stranded in a small water channel,” he explained.

The body was transported to Sukkur for autopsy. The dolphin will be buried in the graveyard dedicated for them located near the sanctuary in Sukkur.

A survey conducted by the SWD in 2019 concluded that the total population of dolphins in canals between Guddu and Sukkur Barrages was 1,419 at the time.

Over two dozen blind dolphins were stranded in Dec 2021

It should be a cause for concern that three rare Indus dolphins have died in less than a month. The first dolphin was caught dead in a fishing net at the Indus Taunsa Barrage; the video of the second went viral on social media but the authorities failed to find it; while the third was found dead under the bridge during the gate closure of Taunsa Barrage.

From 2001 to 2017, NGOs and local communities worked extremely hard and were successfully able to increase the population of these precarious dolphins through community-based conservation efforts. Unfortunately, 2021 has been a rather punishing year as the population of these endangered dolphins has dwindling with each passing month. And the reasons are no secret. The construction of irrigation systems, dams and reservoirs have confined most dolphins to a 750-mile stretch of the river and divided into isolated populations by barrages. Moreover, fishing has proved lethal as fishermen do not follow set protocols and conditions regarding the types of nets, materials, mesh size, etc and overfishing continues unabated. Corruption has also been a huge issue as there is a marked difference between funds given and efforts made. While the incumbent government talks a good game on fighting climate change and conserving biodiversity, nothing significant has been done in trying to protect these rare mammals that are not found anywhere else in the world. The Indus river has already lost its crocodile and otter species, and the same fate will befall these dolphins if timely action is not taken.

Fortunately, previous efforts have shown that progress is possible when governments, conservationists, and communities work together. It is time to rekindle those efforts and work towards creating an ecosystem in which these dolphins are able to self-sustain. While the wildlife and fisheries department can work with local communities at the ground-level, the federal and provincial governments must devise a holistic plan whereby crucial infrastructure is either destroyed or restructured in order to minimise the effects it has on aquatic life and wildlife.

At least 27 Indus blind dolphins have been sighted in various canals of the river downstream the Sukkur Barrage in December 2021, officials of the Sindh Wildlife Department (SWD) said.

Four more endangered Indus blind dolphins have reportedly been sighted in the water canals some 175 kilometres from their homes. Nine dolphins were already sighted at different places of district Larkano, Khairpur and Shikarpur.

The officials posted at Sukkur Indus Dolphin Sanctuary said that the stranded dolphins won’t be rescued because of the current water flow, claiming none of them was under any threat. The Sindh Wildlife Department’s (SWD) officials were informed by the local villagers near Mirwah, a water canal located in Thari Mirwah of district Khairpur, about four dolphins sighted in the canal,” said Sukkur division’s Deputy Conservator Adnan Hamid Khan.

But, he clarified, our team have spotted only three so far. He said that the officials have been deployed for monitoring the moments of the mammals. Khan said that the rescue operation was halted because of the technical reasons.

“It is not possible to bring them back to their home now,” he explained. He said that the rescue team has to wait until the water flow supports the operation. “It’s Kharif crops season,” Khan said. “Everyone needs water to save their drying crops,” he added. “We cannot compel the irrigation department to close the gates,” he said, adding that the mammals were out of danger. “We have to wait patiently.”

Officials claimed that they have spotted 27 dolphins stranded at different locations.

Three in Dadu Canal, three in Mirwah Canal, four in Khirthar Canal, six in Rohri Canal, three in Nara Canal, two in Putt Feeder, four in Ghotki Feeder, and two in the Abul Wah-Khairpur Feeder West. Sources told that two to three more dolphins were sighted at different locations.

The heart-wrenching incident involving the cold-blooded killing of a 20-month-old Indus river dolphin in August 2023 served as a grim reminder of our collective responsibility towards safeguarding the unique and fragile ecosystem of Pakistan. The tragic event not only highlighted the urgent need for intensified conservation efforts but also sheds light on the underlying issues of environmental awareness.

The Indus river dolphin is not just an endangered species and a symbol of Pakistan’s natural heritage; it is also an integral part of the cultural and ecological tapestry of Sindh. Affectionately known as “Susu” in the local language, these dolphins have long been facing an uphill battle for survival due to a range of threats, from habitat degradation to pollution. Beyond the tragic incident itself, the situation underscores the inadequacies in our legal frameworks for wildlife protection. The jurisdictional challenges faced by the Sindh Wildlife Department reveal the pressing need for coordinated efforts among provincial governments to tackle such issues effectively. Collaborative action and a unified approach to wildlife protection are imperative to prevent such wanton acts from recurring. The outpouring of grief and anger on social media is a testament to the profound connection between the Indus river dolphin and the people. The poignant words of Karachi-based artist and activist Zulfikar Ali Bhutto junior remind us that every act of cruelty towards an innocent creature chips away at our own humanity.

Raising awareness among local communities about the significance of these species in maintaining a balanced ecosystem is paramount. Strengthening the enforcement of existing wildlife protection laws and implementing comprehensive conservation programmes can serve as a buffer against such mindless acts. As we mourn the loss of this young dolphin, we must also recognise the urgent need to fortify our commitment to protecting our natural world.