Angeles

Hollywood stars are not the only celebrities who live in the hills around Los Angeles: Southern California’s mountain lions also make their homes there and are sometimes almost as famous. The animal, also known as a puma or a cougar, is the region’s apex predator, and spotting them is like a hobby for locals.

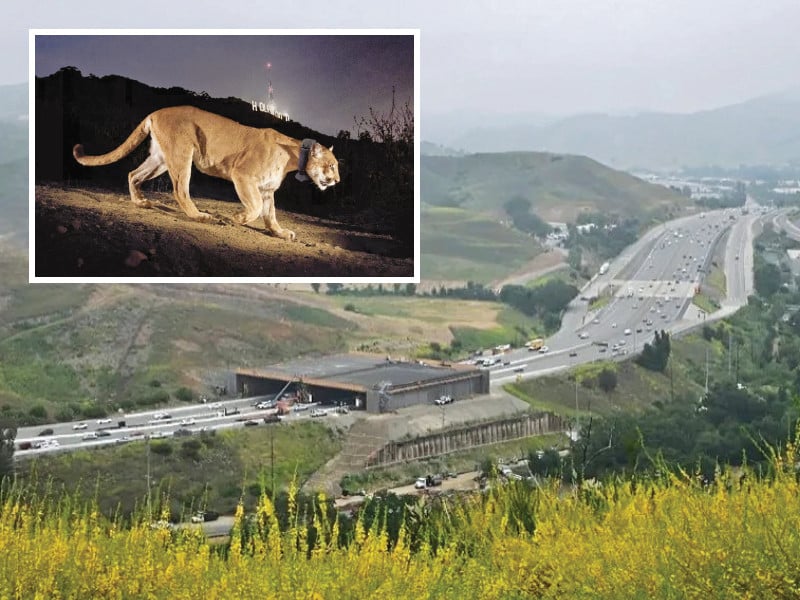

A 2013 photograph of the much loved, but unimaginatively named, P-22 in front of the Hollywood sign cemented the creature’s place in the popular imagination. But the picture also highlighted the difficulties faced by a species whose habitat has been invaded by people, and the growing risks of extreme weather events driven by human-caused climate change.

Mountain lions have “lived here forever, and now we are building homes and facilities out on their property,” Andy Blue of the San Diego Humane Society’s Ramona Wildlife Centre, said. “So it’s inevitable that there’s going to be interaction between them.”

One of the most ambitious efforts to reduce humanity’s impact on mountain lions is taking shape northwest of Los Angeles: the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing. The first phase of the project on track to open in 2025, will see the completion of a bridge for wild animals over 10 lanes of Highway 101, one of the busiest roads in southern California, with over 300,000 daily travelers.

“When the 101 freeway was constructed through this area about 60 years ago, it had the unintended consequence of cutting off all of the Santa Monica Mountains” from another nearby mountain range, said the National Wildlife Federation’s deputy director for California. That separation created what Gill called an “island of habitat, cut off from all of the wild area to the north.”

The consequences of that highway have been significant for the area’s wildlife. Not only did it diminish the genetic diversity of several native species, it also markedly reduced the mountain lions’ usual habitat for hunting and reproducing, putting the animal at risk of an “extinction vortex.

The wildlife crossing, covered by local plants, aims to remedy the problem by reconnecting the mountains and will provide safe passage for the pumas and other fauna in the region. You would not think that birds would need the help of a wildlife crossing,” Gill said. “But in fact, we have some smaller birds like [the] wrentit, who are indigenous to this area, and they are so tiny that the wind currents generated by the freeway make it impossible for them to cross.

According to organizers, once completed, the $80 million project will be the largest wildlife crossing in the world.

The need for a protected zone like the crossing is evident at the Ramona Wildlife Centre, where all kinds of animals from raccoons to bears are nursed back to strength after falling sick or being orphaned or injured.

The mountain lions come into their care for any number of reasons, but most stem from “human-wildlife conflicts.”

One to two mountain lions are struck by cars a week in California, and it’s the number one reason for mountain lion deaths in the state. The public need to be better educated about how to interact with animals.

Wildlife photographer Johanna Turner, who uses remote cameras to capture animals in their natural habitat, said it does not take much to make the area around Los Angeles safer for mountain lions. “I just want people to know how lucky they are to have this wildness, and it can go away,” Turner said from a hill overlooking the city’s skyline. “It can end so fast.”

When P-22 died in December 2022 the outpouring of grief ended up being a wake-up call for Los Angeles. Then in June 2024, as often happens in Tinseltown, a new star was born when a Hollywood Hills resident captured images of another mountain lion before it disappeared into Griffith Park. “We are so used to tragic stories about wildlife and having just to give up and say, ‘This is a city… It just cannot be that way here,’” Turner said. “P-22 showed us it absolutely can.”